- Inner Harmony Yoga

- Ayurveda, yoga, Missoula, lecture, Devi Zdziebko

- brian baty

- gurnam singh, Inner Harmony yoga, Missoula, kirtan,

- Juliet Jivanti, Ayurveda, Yoga, Missoula

- Meditation, yoga, missoula yoga, Gina Mauro

- Missoula yoga

- Missoula yoga, Erich Schiffmann, yoga, workshop, Inner Harmony Yoga

- yoga

- yoga, Advanced yoga

- yoga, back bends, flexability, strength, Missoula

- yoga, hip openers, flexability, Missoula

- yoga, Missoula, 108 sun salutations, Inner Harmony

- yoga, Missoula, retreat, Inner Harmony yoga, back bends, flexablity, bootcamp, yoga retreat

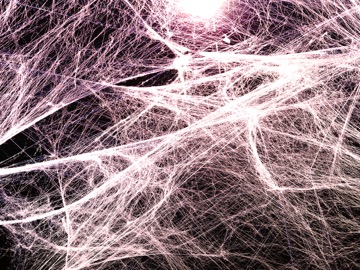

The Fascia that Binds

13/03/18 16:25

When we talk about fascia, it is important to reference the idea of stability. What is more stable? A bridge with eight pillars supporting it on either side, or a bridge with one single pillar supporting it? Common sense tells us that eight pillars will absolutely be a more stable design. Anything with more support or cushion or more...stuff...around it is going to have more stability. Where our bodies are concerned, a joint that is supported by tissue is going to be a safer, more stable joint. The body wants to create stability to prevent or recover from injury. It sees immobility as possible injury and it works quickly to support what isn’t moving in order to facilitate the healing it assumes is needed based on the information it has been given; in this case, lack of movement. The stuff that is responsible for that stability, or stiffness, is a strong webbing of connective tissue called fascia. We need this tissue in the correct balance in order to maintain stability and strength in our joints. Without it, our joints would not be able to support our bodies and injury would soon follow. Tendons are fascia, ligaments are fascia, our knees, elbows, wrists and spines are all supported in their movement by the connective bonds of fascia. However, as important as fascia is, it has no blood flow. This is why injury to our ligaments or tendons take longer to heal than broken bones do. Our bones have blood flow, and that vital circulation offers somewhat speedy recovery.

When stuff stops moving--say it’s your lower lumbar or sacrum--the layers of fascia are going to get thicker and thicker over time. When that happens, this blood-free tissue essentially squeezes the moisture out of the area and suffocates the ability to move. We get locked up. We stiffen. Touching our toes gets more difficult. As we lose our mobility in one area, other areas follow. We begin to hunch as the fascia binds us into the still position we hold in front of our computers. Our hamstrings tighten, bound in a shortened seated position by our well-meaning fascia. It happens a lot nowadays because many of us are largely sedentary in our daily lives due to desk jobs and repetitive motion (or no motion) tasks that isolate one part of the body, neglecting the

rest.

When we don’t move, when we go to bed and hold still for eight hours in slumber, the body’s primary functions are still at work. Our body scans itself and finds where we aren’t moving, and even though sleep is not an injury, the information of stillness is obtained, and the body responds to it by wrapping a thin layer of fascia around the joints and the muscles in order to better support that which isn’t moving. When we wake up, we feel a little stiff, and so we stretch out the body, which in turn breaks apart the fascia and allows, once again, for more fluid mobility. But, let’s say we suffer an injury and stretching isn’t possible because of the pain experienced with mobility. When that happens, you can’t just stretch and tear through the fascia...so, the layers of fascia begin to stack. One layer becomes two, and then four and then ten. Days and weeks of reduced mobility send a message to continue the stabilization of the muscles and joints to create strength where there is weakness. Over time, the body heals, and once that happens, and the brace comes off, or the order to reduce motion has been lifted by our caregiver, we find that we don’t have the range of motion we used to have. We lose that, because the body is skillfully supporting itself with fascia in order to protect itself from further injury; Something that doesn’t move is more stable than something that does move.

When we see a cat stretch, we are seeing them keep their nimble flexibility with fluid movement whenever they rise. That might be several times a day. They have fascia...they wake up and they stretch boldly, tearing through the fascia that binds them. The cat knows that if it is to retain its stamina and flexibility, it must stretch its entire body. So, that’s one of the reasons we come to our mat...so we can break through some of that fascia that we are constantly making in stillness. Because the body never stops producing fascia, we offer it guidance as we show the body a complete range of motion on our mat, breaking through fascia we don’t need, gaining strength and flexibility in supporting muscle tissue, and creating a practice that informs the body and protects it from overproduction of connective tissue that, unchecked, ages us physically into bodies that can no longer enjoy fluidity of movement. This particular aging process is not inevitable. We can defy it with our yoga practice. We can break through the fibers that literally bind us, strengthening and offering ourselves the promise of flexible, healthy bodies that support us without hindering as we walk through our lives.

We feel better when we move. When we feel better, we behave better; we are kinder, softer, calmer. Our nervous systems are less frazzled and our mood elevates. This is what yoga gives us. All we need to do is to come to our mats...and move.

Namaste’.

- Inner Harmony Yoga

- Ayurveda, yoga, Missoula, lecture, Devi Zdziebko

- brian baty

- gurnam singh, Inner Harmony yoga, Missoula, kirtan,

- Juliet Jivanti, Ayurveda, Yoga, Missoula

- Meditation, yoga, missoula yoga, Gina Mauro

- Missoula yoga

- Missoula yoga, Erich Schiffmann, yoga, workshop, Inner Harmony Yoga

- yoga

- yoga, Advanced yoga

- yoga, back bends, flexability, strength, Missoula

- yoga, hip openers, flexability, Missoula

- yoga, Missoula, 108 sun salutations, Inner Harmony

- yoga, Missoula, retreat, Inner Harmony yoga, back bends, flexablity, bootcamp, yoga retreat